This review was originally published on Mind Equals Blown.

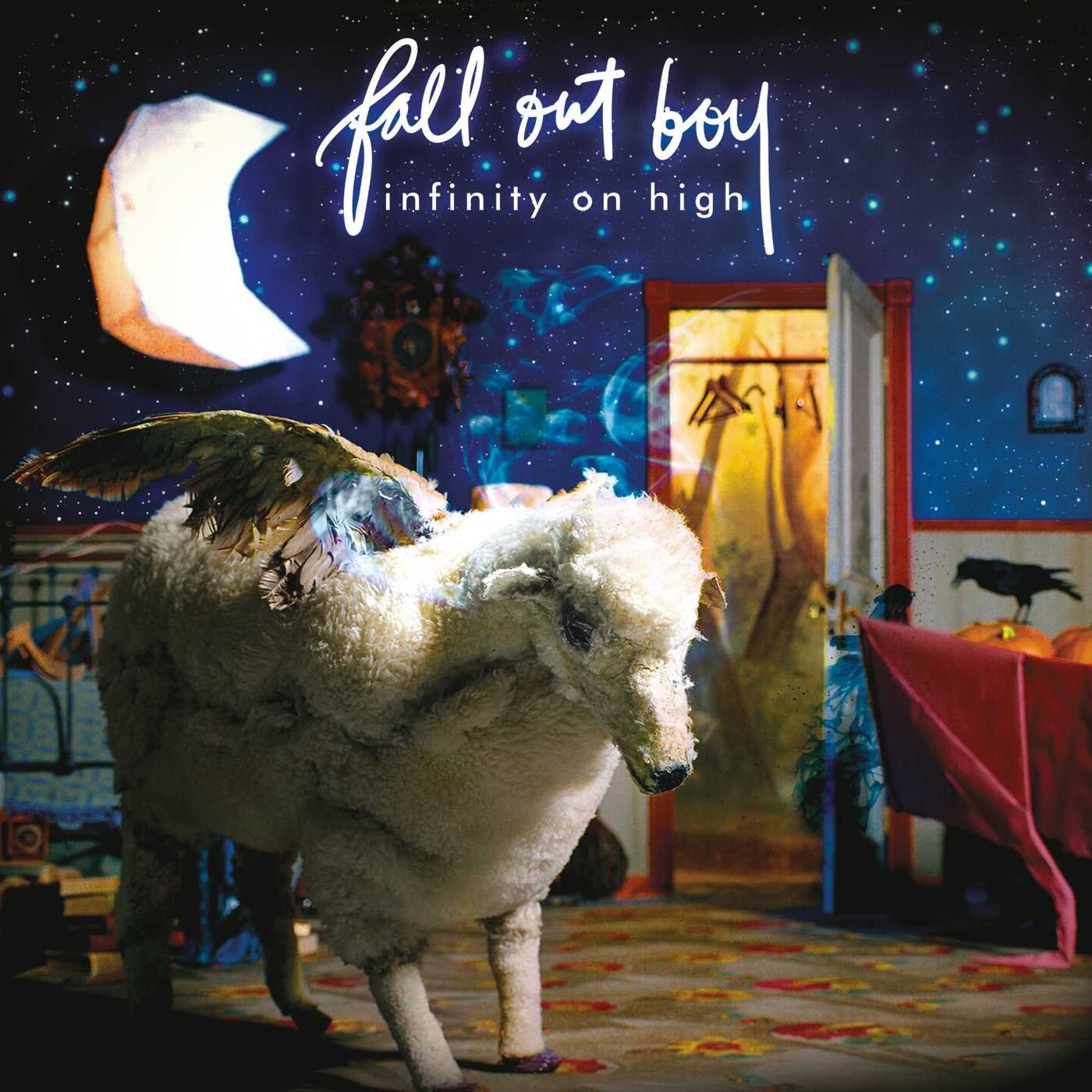

What is “good” is totally subjective. I stand by that with a firm resolve. I write reviews with apprehension because of this fact. What is deemed quality by one can easily disregarded by another for any array of criticisms. I have even found such conflicting thoughts in myself over periods of time. Such is the case with Fall Out Boy’s 2007 effort, Infinity On High, the album I grew to adore.

I’ve written at length about the effects Fall Out Boy’s From Under the Cork Tree has had on me. It acted as a path, a musical bridge from childhood listening to young adulthood discovery. Thus, the P.E. gym bar was set in its highest notch for any subsequent releases from Fueled By Ramen’s golden boys. Upon its release, I found that Infinity On High not only failed to do a pull-up, it couldn’t even reach the bar.

From my first listen to the now-infamous introduction by hip-hop mogul Jay-Z, I was skeptical. Despite some lent-hands on From Under the Cork Tree by the likes of “pop-punk” icons Chad Gilbert, Brendon Urie, and William Beckett, I didn’t think of Fall Out Boy as a band that required album features to sell a quality record, especially out of their “scene.” Having the follow-up to my favorite record introduced by a rap star like Hova was bold. Too bold for my 8th grade nostalgic self.

As my final middle school year progressed, so did my taste. I expanded into new markets. Some lighter, most heavier. I all but forgot about Jay-Z’s breathy in-your-face spoken word and Fall Out Boy’s new album. That was, of course, until the trip and if you’re from anywhere east of Chicago, you most likely know which one I’m referring to. My 8th grade class trip to Washington DC changed the way I thought and felt about Infinity On High in a profound and lasting way.

Before iPod shuffles made their way into the hands of most of my classmates the next year, I recall a wide assortment of portable music players making their way around the charter bus. At that time, I had a Creative ZEN Nano (later followed by the MuVo and ZEN), and it only had 256MB of space. Ahead of departure, I glanced through my Musicmatch Jukebox for travel tunes. Lo and behold, there sat Infinity On High awaiting a second chance from a youthful critic’s ear. I loaded it on and loaded on the bus.

Sparing you from the fond, but admittedly unimpressive and occasionally embarrassing memories that I banked on that vacation, we’ll skip to track two of the record. “The Take Over, The Break’s Over” is a snarky song. I thought so then, I believe so now. This was far from a bad thing, but it wasn’t what brought me back around. What captured my attention on that yellow dress audit was the pre-chorus. “Don’t pretend you ever forgot about me.” It was then I fell back in love with Patrick Stump’s incredible vocal and the words Wentz lent to it.

Middle school does things to a boy, it brings up… feelings. Those desperate, unrequited, adolescent feelings that make those less socially awkward cringe. Being one of those poor schlubs when this album was released, I connected. The lyrical content of the record was dark. It was bitter. It was desperate. I didn’t have much for Internet access back then and Absolutepunk.net and LiveJournal certainly weren’t exactly my online hangouts when I did. Naturally, I had no idea of the trials in Wentz’s life. Still, I bonded. Likening my childish problems to a set far more adult.

On that trip, I fell in love with several songs more-so than others. Songs I think permanently changed my taste. “I’m Like a Lawyer with the Way I’m Always Trying to Get You Off (Me & You)” is a stroke of brilliance. Babyface’s production credit set the grounds for that. There was a very different sound emanating from those instruments there. One I couldn’t then explain, but one I think was the first real step to what would come with Folie à Deux.

“Hum Hallelujah” was an instant favorite, of course sampling one of the most iconic songs ever written, a tune that Pete Wentz and many others have cited as a literal lifesaver. Cohen lent itself perfectly to the bridge. “Don’t You Know Who I Think I Am?” put that much-needed touch of Butch Walker magic in the mix. I’m now convinced that all he touches is gold.

“The (After) Life of the Party” was one I particularly loved on that trip across Pennsylvania’s plains. I often think back to find myself staring out of that bus window, taking in the monuments as I approached our Nation’s Capitol. It was one of those moments of pure synchronicity, a memory and a song forever bound in my mind.

Further, “Bang the Doldrums” provoked a notion of urgency and excitement in a new way, far apart from their back catalogue. Truthfully, I could have done without the bit of Pete’s poetry, but that goes for every album and equally tarnishes each in a familiar sort of way. (Do not get me wrong, some days I love those parts.)

While the first half was catchy and solid, I found the latter half didn’t catch much of my attention. My current self feels that it hasn’t held up quite as nicely as I would have liked. “The Carpal Tunnel of Love” feels unfinished everywhere but the chorus, “Fame < Infamy” does little more than incite some violent toe-tapping, and “You’re Crashing, But You’re No Wave” has its shining moments in the chorus, but falls flat in the narrative. The lead-out, “I’ve Got All This Ringing in My Ears and None on My Fingers” picked things up by a small degree, not entirely saving the back-half of the album, but at least sending it off with a fond farewell.

After it all, it’s the ever-controversial “Golden” that adequately summarizes my feeling for the entire record. On my DC trip, this was not only my least favorite song on Infinity On High, but in the entire Fall Out Boy discography. Since then, I’ve reconsidered it, listened to it dozens of times over and placed it amongst my prized favorites.

The writing on Infinity On High was superb. Inspired by idols in his hardcore roots and having dealt with some of the most difficult times of hardship he would face in his life, Wentz wrote what is debatably (and I go back and forth on this monthly) Fall Out Boy’s best record.

I’m happy that I grew into this album. Had I not found a piece of myself in Infinity On High, I think my current tastes would differ, I’d be writing less, and those long Midwestern hours in the second row from the back wouldn’t have been as enjoyable as the ultimately were.